Our Cats

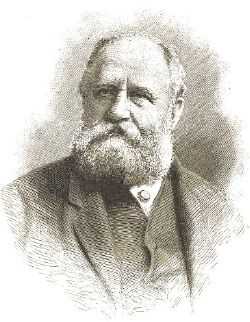

By Harrison Weir, printed in 1889.

Here we present a few chapters from "Our Cats", written by Harrison Weir in 1889. The drawings of the cats in his book were also made by him.

Harrison Weir was the one who arranged the first cat show in England, in Crystal Palace, London, 1871. He was also the one who wrote the first standards for the different varieties of cats.

Chapters

Prefaces, 1st edition (1889) and 2nd edition (1892)

Preface, 1889

"What is aught, but as 'tis valued?"

Troilus and Cressida, Act II.

The following notes and illustrations of and respecting the Cat are the outcome of over fifty years' careful, thoughtful, heedful observation, much research, and not unprofitable attention to the facts and fancies of others. From a tiny child to the present, the love of Nature has been my chief delight; animals and birds have not only been objects of study, but of deep and absorbing interest. I have noted their habits, watched their ways, and found lasting pleasure in their companionship. This love of animal life and Nature, with all its moods and phases, has grown with me from childhood to manhood, and is not the least enjoyable part of my old age.

Among animals possibly the most perfect, and certainly the most domestic, is the Cat. I did not think so always, having had a bias against it, and was some time coming to this belief; nevertheless, such is the fact. It is a veritable part of our household, and is both useful, quiet, affectionate, and ornamental. The small or large dog may be regarded and petted, but is generally useless; the Cat, a pet or not, is of service. Were it not for our Cats, rats and mice would overrun our house, buildings, cultivated and other lands. If there were not millions of Cats, there would be billions of vermin.

Long ages of neglect, ill-treatment, and absolute cruelty, with little or no gentleness, kindness, or training, have made the Cat self-reliant; and from this emanates the marvellous powers of observation, the concentration of which has produced a state analogous to reasoning, not unmixed with timidity, caution, wildness, and a retaliative nature.

But should a new order of things arise, and it is nurtured, petted, cosseted, talked to, noticed, and trained, with mellowed firmness and tender gentleness, then in but a few generations much evil that bygone cruelty has stamped into its often wretched existence will disappear, and it will be more than ever not only a useful, serviceable helpmate, but an object of increasing interest, admiration, and cultured beauty, and, thus being of value, profitable.

Having said this much, I turn to the pleasurable duty of recording my deep sense of the kindness of those warm-hearted friends who have assisted me in "my labour of love," not the least among these being those publishers, who, with a generous and prompt alacrity, gave me permission to make extracts, excerpts, notes, and quotations from the following high-class works, their property. My best thanks are due to Messrs. Longmans & Co., Blaine's "Encyclopaedia of British Sports;" Allen & Co., Rev. J. F. Thiselton Dyer's "English Folk-lore;" Cassell & Company (Limited), Dr. Brewer's "Dictionary of Phrase and Fable," and "Old and New London;" Messrs. Chatto & Windus, "History of Sign-boards;" Mr. J. Murray, Jamieson's "Scottish Dictionary," and others. I am also indebted to Messrs. Walker & Boutal, and The Phototype Company, for the able manner in which they have rendered my drawings; and for the careful printing, to my good friends Messrs. Charles Dickens & Evans.

HARRISON WEIR.

"IDDESLEIGH," SEVENOAKS,

May 5th, 1889.

Preface To New Edition (1892)

"'Twas pitiful, 'twas wondrous pitiful."

Othello.

Some time has passed since I published my book, "Our Cats and all about them," in 1889, and much has taken place regarding these household pets. All know as well as myself that each and everything about us changes, nothing stands still; that which is of to-day is past, and that which was hidden often revealed, sometimes by mere accident, at others by scientific research; but one was scarcely prepared in any way for so wonderful "a find" as that of the large number of "mummy" Cats at Beni Hassan, Central Egypt. They were discovered by an Egyptian fellah, employed in husbandry, who tumbled into a pit which, on further examination, proved to be a large subterranean cave completely filled with mummy Cats, every one of which had been separately embalmed and wrapped in cloth, after the manner of the Egyptian human mummies, all being laid out carefully in rows; and here they had lain probably about three or four thousand years. The "totem" of a section of the ancients, as is well known, was the Cat; hence when a Cat died it was buried with due honours, being embalmed, and often decorated in various ways, and, in short, had as much attention paid to it as a human being. It had long been believed that a Cat cemetery existed on the east bank of the Nile, and in the autumn of 1889 the lucky Egyptian, about 100 miles from Cairo, came unexpectedly upon it.

Immediately on "the find" becoming known, "specimen" mummy Cats were written for to agents in Egypt, one friend of mine sending for four, and it appeared for a while that much money would be realised by the owner of the cave or land in this way; but the number was too great, and the prices and the interest gave way, and, sad to relate, these former "Deities" were dug out of their resting-place by hundreds of thousands, and quickly sold to local farmers, being used for enriching the land. Other lots found their way to an Alexandrian merchant, and were by him sent to Liverpool on board the steamer Pharos and Thebes.

The consignment consisted of 19 ½ tons, and were sold by auction, mostly being bought by a local "fertiliser" merchant. The auction was only known to the trade, and the lots were "knocked down" at the "giving away" sums of £3 13s. 9d., £3 17s., to £4 5s. per ton, the big and the perfect ones being picked out for the museum and private collections. The broker who sold used a head of one of these Cats in lieu of an auctioneer's hammer. And now these tons of "deified" Cats are used for manure, and in our English soil plants grow into them, and on them, and of them; and, if it be true, as chemists assert, these plants take into their system that on which they feed, and so, if so, possibly in our very bread that we have eaten, we have swallowed "a little at a time part of if not the whole of a deified cat."

I made several endeavours to find out from those on the spot at Liverpool whether there was any hair of colours in existence among the mass of bodies; but in no case could I succeed in getting any, as I had hoped by this means to possible come to some conclusion as to the kind or breed. Of course, it is well known from mummies long in this country what form, size, and general appearance the Egyptian possessed; but as yet, as far as I can learn, no one has found so much, if any, of the fur as to be able to determine the colour.

Apropos with the above, as applying the bodies of the mummy Cats for manure, comes the modern idea of keeping Cats for their fur. It is stated that a company has been formed in America for that purpose in Washington, and an island of some size has been bought or leased for the purpose. The intention is to raise entirely black Cats; and as their place of abode will be surrounded by water, it is conjectured that after the first importation they will go on propagating and producing only Cats of that beautiful though sombre dark hue. The Cats with which the island is to be stocked are to be procured from Holland, where already the "industry" is "at work." So much so that a friend of mine, an elderly gentleman, sending to a furrier in Holland to know what kind of fur he would recommend as the best for warmth, received the reply that Cats' skins "were the most useful and warmest." A few days ago he called on me wrapped in a cloth coat, with fur collar and cuffs, and lining throughout of black Cats' skins, and I am bound to say that the general appearance was much in its favour; he also stated that he was in every way perfectly satisfied.

By-the-bye, the Cat Company intend to feed their Cats on fish, which abound about the shores of their island, and so they affirm the food will cost nothing, and their profits consequently be very large. But in this I hope they have been well informed as to the adaptability of the Cat to feed entirely on fish, for of this I have my doubts; certainly those I have had did not appear to thrive if they had fish too often.

Again, as the Cats are to roam the island at their "own sweet will," I take it there will be at times some "damaging of fur" by the playful way in which they so often engage, when jealousy incites them to mortal combat. But possibly this has been considered and duly entered in the "profit and loss" account.

While writing that portion of my book in which I referred to tne superstitions connected with the domestic Cat, and the amazing stories told of the witches' Cats, I felt convinced that in those darkened and foolish times that the very fact of the wonderful faculty the Cat possesses of applying what it observes to its own purposes was in some way the cause of the ignorant and superstitious considering that it was "possessed" of an evil spirit. I therefore searched for proofs among the evidence given at the trial of witches, and was, as I expected, rewarded for my trouble. What a Cat would do now would not unreasonably be thought clever and showing much sagacity, if not attributes of a deeper kind.

Yet I find that at a trial for witchcraft, the following questions were put to a man: "Well! and what did you see?" "Well! I saw her Cat walk up and try to open the door by the latch." "What did you do?" "I immediately killed it." This, which is now regarded as an everyday example of the intelligence of the Cat, bore hardly in the evidence against the witch. Sir Walter Scott, in his letter on "Demonology and Witchcraft," tells of "a poor old woman condemned, as usual, on her own confession, and on the testimony of a neighbour, who deposed that he saw a Cat jump in the accused person's cottage through the window at twilight, one evening, and that he verily believed the Cat to be the devil, on which precious testimony the poor wretch was hanged." One more note and I leave the subject. A certain carpenter, named William Montgomery, was so infested with Cats, which, as his servant-maid reported, "spoke among themselves," that he fell in a rage upon a party of these animals, which had assembled in his house at irregular hours, and betwixt his Highland arms of knife, dirk, and broadsword, and his professional weapon of an axe, he made such a dispersion that they were quiet for the night. In consequence of his blows two witches are said to have died.

Since writing of the English wild Cat, I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Francis Darwin (brother of Mr. Charles Darwin) on board the steamboat going to St. Servan, when, in the course of conversation, he informed me that a wild Cat was killed at Bramhope Moor Plantation, in 1841, a keeper having caught it in two traps.

In February of this year, 1891, my kind friend, Mr. Dresser, of Orpington, the well-known naturalist, wrote to me to know whether I would like to have a kitten half-bred between the British Wild Cat and a domestic she Cat, which I was unfortunately obliged to decline, fearing it would "make matters unpleasant" with what I had. He very kindly supplied me with the following particulars forwarded to him by 0. H. Mactheyer, Esq.: " Mr. Harrison Weir can see the papa of the kitten at the Zoo.

"He is a young Cat (under a year old, we thought, by the teeth). He was seen one moonlight night in company with my 'stalker's' small lean black Cat, right away in my deer forest. We caught the papa in a trap after he had killed a number of grouse, and not being badly hurt, I sent him to Bartlett at the Zoo. We are thoroughly up to real wild Cats here. I have caught them forty-three inches from nose to tail-end; tails as thick at the point as at the root; the ears are also differently set on. Martin Cats, Polecats, and Badgers are all extinct here, and it is ten years since we got the last wild Cat, but three have been killed in this district this winter."

I insert the foregoing as being of much interest, it having been frequently stated that the wild Cat will not mate with the domestic Cat. The kitten offered to me is now at Fawley Court, Bucks.

Among the numerous letters I have received from America is one from Mrs. Mary A. C. Livermore, of Cambridge, Mass., U.S.A., who writes: "I have just come possessed of a black long-haired Cat from Maine. It is neither Persian, Angora, nor Indian. They are called here 'Coon' Cats, and it is vulgarly supposed to be a cross between a common Cat and a 'Coon.' Mine is a rusty bear-brown colour, but his relatives have been black and white, blue and white, and fawn and white, the latter the gentlest, prettiest Cat I know. His tail is very bushy and a fine ruff adorns his neck. A friend of mine has a pair of these Cats, all black, and the female consorts with no one but her mate. Yet often she has in her litter a common short-haired kitten."

Since the above reached me, I have received from another correspondent in the United States a very beautiful photograph of what is termed a "Coon" Cat. It certainly differs much from the ordinary long-haired Cat in appearance; but as to its being a cross with the Racoon, such a supposition is totally out of the question, and the idea cannot be entertained. The photographs sent to me show that the ears are unusually large, the head long, the length being in excess from the eyes to the tip of the nose, the legs and feet are large and evenly covered with long, somewhat coarse hair, the latter being devoid of tufts between and at the extremity of the toes; there are no long hairs of any consequence either within the ears or at their apex. The frill or mane is considerable, as is the length of the hair covering the body; the tail is rather short and somewhat thick, well covered with hair of equal length, and in shape like a fox's brush. The eyes are large, round, and full, with a wild staring expression. Certainly, the breed, however it may be obtained, is most interesting to the Cat naturalist, and the colour, as before stated, being peculiar, must of course attract his attention independently of its general appearance.

Since the above was written, I have received the following from Mr. Henry Brooker, The Elms, West Midford, Massachusetts, United States of America. After asking for information respecting Cats of certain breeds, he says:

"I have had for a number of years a peculiar strain of long-haired Cats; they come from the islands off the coast of Maine, and are known in this country as 'Coon' Cats. The belief is that they have been crossed with the 'Coon.' This, of course, is untrue. The inhabitants of these islands are seafaring people, and many years ago some one on his vessel had a pair of long-haired Cats from which the strain has sprung. There are few short-haired cats on the island as there is no communication with the mainland except by boat. I want to improve my strain and get finer hair than the Cats now have. Yellow Cats are the most popular kind here, and I have succeeded in producing Cats of a rich mahogany colour with brushes like a fox. They hunt in the fields with me, and my Scotch terriers and they are on the most friendly terms." This, as a corroboration of the foregoing letters and the photographs, is, I take it, eminently satisfactory.

I have been shown a Siberian Cat, by Mr. Castang, of Leadenhall Market; the breed is entirely new to me. It is a small female Cat of a slaty-blue colour, rather short in body and legs; the head is small and much rounded, while the ears are of medium size. The iris of the eyes is a deep golden colour, which, in contrast to the bluish colour of the fur, makes them to appear still more brilliant; the tail is short and thick, very much so at the base, and suddenly pointed at the tip. It is particularly timid and wild in its nature, and is difficult to approach; but, as Mr. Castang observed, this timidity may be "because it does not understand our language and does not know when it is called or spoken to." I think it would make a valuable Cat to cross with some English varieties.

A correspondent writes: "In your book on Cats you do not mention Norwegian Cats. I was in Norway last year, and was struck by the Cats being different to any I had ever seen, being much stouter built, with thick close fur, mostly sandy, with stripes of dark yellow." I suppose I am to infer that both the sexes are of sandy yellow colour. If so, I should say it is more a matter of selection than a new colour. I find generally in the colder countries the fur is short, dense, and somewhat woolly, and as a rule, judging from the information that I am continually receiving, whole or entire colours predominate.

Large Cats are by some sought after. This, I take it, is a great mistake, the fairly medium-sized Cat being much the handsomer of the two, and they are generally also devoid of that coarseness that is found apparent in the former; while small Cats are extremely pretty, and I understand are not only likely to be "in vogue," but are actually now being bred for their extreme prettiness. I have heard of some of these "Bantam" Cats being produced by that true and most excellent fancier, Mr. Herbert Young, who not only has produced a Tortoiseshell Tom Cat on lines laid down by myself, but is also engaged in breeding more, and I have not the least doubt he will be most successful, he having so been in producing new colours and some of the finest silver tabby short-haired Cats as yet seen; these short-haired Cats, in my opinion, far surpassing for beauty any long-hair ever exhibited, and are certainly of a "sweeter disposition."

In my former edition of "Our Cats," I wrote hopefully and expectantly of much good to be derived from the institution of the so-called National Cat Club, and of which I was then President; but I am sorry to say that none of those hopes or expectations have been realised, and I now feel the deepest regret that I was ever induced to be in any way associated with it. I do not care to go into particulars further than to say I found the principal idea of many of its members consisted not so much in promoting the welfare of the Cat as of winning prizes, and more particularly their own Cat Club medals, for which, though offered at public shows, the public were not allowed to compete, and when won by the members, in many cases the public were thoughtlessly misled by believing it was an open competition. I therefore felt it my duty to leave the club for that and other reasons. I have also left off judging of the Cats, even at my old much-loved show at the Crystal Palace, because I no longer cared to come into contact with such "Lovers of Cats."

I am very much in favour of the Cats' Homes. The one at Dublin, in which Miss Swift takes so much interest; the one in London, with Miss Mayhew working for it with the zeal of a true "Cat lover"; and that where Mr. Colam is the manager, all deserve and have my sincerest and warmest approbation, sympathy, and support, standing out as they do in such bright contrast to those self-styled "Cat lovers," the National Cat Club.

HARRISON WEIR, F.R.H.S.

SEVENOAKS,

March 12th, 1892.

Introductory and The First Cat Show

Introductory

After a Cat Show at the Crystal Palace, I usually receive a number of letters requesting information. One asks:

"What is a true tortoiseshell like?" Another: "What is a tabby?" and yet another: "What is a blue tabby?" One writes of the "splendid disposition" of his cat, another asks how to cure a cat scratching the furniture, and so on.

After much consideration, and also at the request of many, I have thought it best to publish my notes on cats, their ways, habits, instincts, peculiarities, usefulness, colours, markings, forms, and other qualities that are required as fitting subjects to exhibit at what is now one of the instituted exhibitions of "The land we live in," and also the Folk and other lore, both ancient and modern, respecting them.

It is many years ago that, when thinking of the large number of cats kept in London alone, I conceived the idea that it would be well to hold "Cat Shows," so that the different breeds, colours, markings, etc., might be more carefully attended to, and the domestic cat, sitting in front of the fire, would then possess a beauty and an attractiveness to its owner unobserved and unknown because uncultivated heretofore. Prepossessed with this view of the subject, I called on my friend Mr. Wilkinson, the then manager of the Crystal Palace. With his usual businesslike clear-headedness, he saw it was "a thing to be done." In a few days I presented my scheme in full working order: the schedule of prizes, the price of entry, the number of classes, and the points by which they would be judged, the number of prizes in each class, their amount, the different varieties of colour, form, size, and sex for which they were to be given; I also made a drawing of the head of a cat to be printed on black or yellow paper for 'a posting bill. Mr. F. Wilson, the Company's naturalist and show manager, then took the matter in charge, worked hard, got a goodly number of cats together, among which was my blue tabby, "The Old Lady," then about fourteen years old, yet the best in the show of its colour and never surpassed, though lately possibly equalled. To my watch-chain I have attached the silver bell she wore at her début.

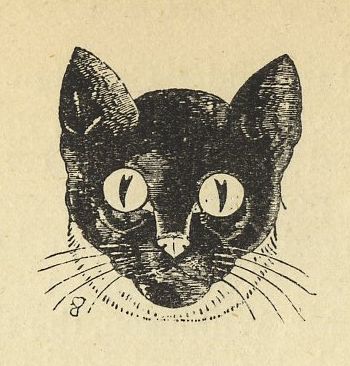

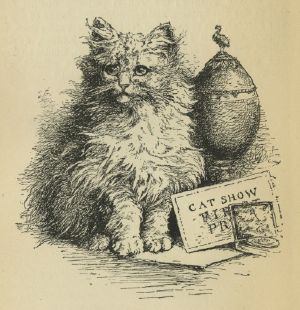

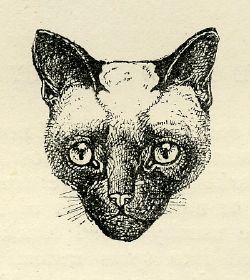

A reduction of the large black Cat's Head,

drawn for the Posting Bill giving notice of the first

Cat Show at the Crystal Palace, July 16, 1871.

My brother, John Jenner Weir, the Rev. J. Macdona, and myself acted as judges, and the result was a success far beyond our most sanguine expectations - so much so that I having made it a labour of love of the feline race, and acting "without fee, gratuity, or reward," the Crystal Palace Company generously presented me with a large silver tankard in token of their high approval of my exertions on behalf of "the Company," and - Cats. Now that a Cat Club is formed, shows are more numerous, and the entries increasing, there is every reason to expect a permanent benefit in every way to one of the most intelligent of (though often much abused) animals.

Silver Tankard presented by the

Crystal Palace Company to the Author

The First Cat Show

On the day for judging, at Ludgate Hill I took a ticket and the train for the Crystal Palace. Sitting alone in the comfortable cushioned compartment of a "first class," I confess I felt somewhat more than anxious as to the issue of the experiment. Yes; what would it be like? Would there be many cats? How many? How would the animals comport themselves in their cages? Would they sulk or cry for liberty, refuse all food? or settle down and take the situation quietly and resignedly, or give way to terror? I could in no way picture to myself the scene; it was all so new. Presently, and while I was musing on the subject, the door was opened, and a friend got in. "Ah!" said he, "how are you?" "Tolerably well," said I; "I am on my way to the Cat Show." "What!" said my friend, "that surpasses everything! A show of cats! Why, I hate the things; I drive them off my premises when I see them. You'll have a fine bother with them in their cages! Or are they to be tied up? Anyhow, what a noise there will be, and how they will clutch at the bars and try and get out, or they will strangle themselves with their chains." "I am sorry, very sorry," said I, "that you do not like cats. For my part, I think them extremely beautiful, also very graceful in all their actions, and they are quite as domestic in their habits as the dog, if not more so. They are very useful in catching rats and mice; they are not deficient in sense; they will jump up at doors to push up latches with their paws. I have known them knock at a door by the knocker when wanting admittance. They know Sunday from the week-day, and do not go out to wait for the meat barrow on that day; they - -" "Stop," said my friend, "I see you do like cats, and I do not, so let the matter drop." " No," said I, "not so. That is why I instituted this Cat Show; I wish every one to see how beautiful a well-cared-for cat is, and how docile, gentle, and - may I use the term? - cossetty. Why should not the cat that sits purring in front of us before the fire be an object of interest, and be selected for its colour, markings, and form? Now come with me, my dear old friend, and see the first Cat Show."

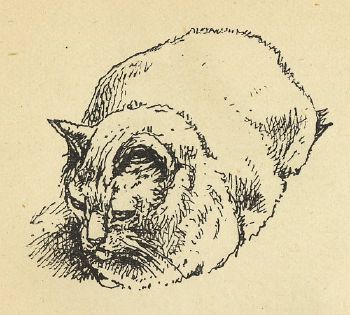

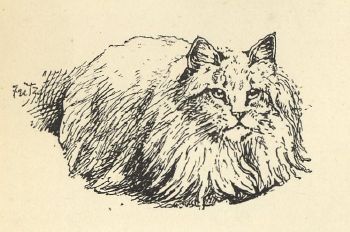

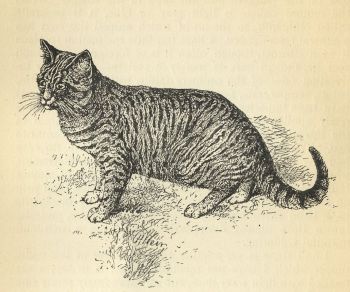

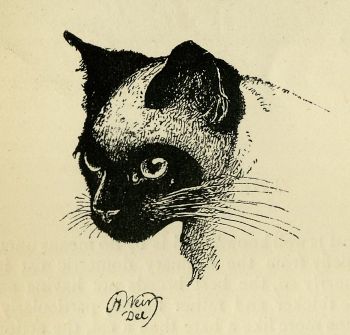

Cat at Show

Inside the Crystal Palace stood my friend and I. Instead of the noise and struggles to escape, there lay the cats in their different pens, reclining on crimson cushions, making no sound save now and then a homely purring, as from time to time they lapped the nice new milk provided for them. Yes, there they were, big cats, very big cats, middling-sized cats, and small cats, cats of all colours and markings, and beautiful pure white Persian cats; and as we passed down the front of the cages I saw that my friend became interested; presently he said: "What a beauty this is! and here's another!" "And no doubt," said I, "many of the cats you have seen before would be quite as beautiful if they were as well cared for, or at least cared for at all; generally they are driven about and ill-fed, and often ill- used, simply for the reason that they are cats, and for no other. Yet I feel a great pleasure in telling you the show would have been much larger were it not for the difficulty of inducing the owners to send their pets from home, though you see the great care that is taken of them." "Well, I had no idea there was such a variety of form, size, and colour," said my friend, and departed. A few months after, I called on him; he was at luncheon, with two cats on a chair beside him - pets I should Say, from their appearance.

This is not a solitary instance of the good of the first Cat Show in leading up to the observation of, and kindly feeling for, the domestic cat. Since then, throughout the length and breadth of the land there have been Cat Shows, and much interest is taken in them by all classes of the community, so much so that large prices have been paid for handsome specimens. It is to be hoped that by these shows the too often despised cat will meet with the attention and kind treatment that every dumb animal should have and ought to receive at the hands of humanity. Even the few instances of the shows generating a love for cats that have come before my own notice are a sufficient pleasure to me not to regret having thought out and planned the first Cat Show at the Crystal Palace.

Rats, Mice, and Cats

That cats may be trained to respect the lives of other animals, and also birds on which they habitually feed, is a well-known fact. In proof of this I well recollect a story that my father used to tell of "a happy family" that was shown many years ago on the Surrey side of Waterloo Bridge. Their abode consisted of a large wire cage placed on wheels. In windy weather the "breezy side" was protected by green baize, so draughts were prevented, and a degree of comfort obtained. As there was no charge for "the show," a box was placed in front with an opening for the purpose of admitting any donations from those who felt inclined to give. On it was written "The Happy Family - their money-box." The family varied somewhat, as casualties occurred occasionally by death from natural causes or sales. Usually, there was a Monkey, an Owl, some Guinea-pigs, Squirrels, small birds, Starlings, a Magpie, Rats, Mice, and a Cat or two. But the story? Well, the story is this. One day, when my father was looking at "the happy family," a burly-looking man came up, and, after a while, said to the man who owned the show: "Ah! I don't see much in that. It is true the cat does not touch the small birds [one of which was sitting on the head of the cat at the time], nor the other things; but you could not manage to keep rats and mice in there as well." "Think not?" said the showman. "I think I could very easily." "Not you," said the burly one. "I will give you a month to do it in, if you like, and a shilling in the bargain if you succeed. I shall be this way again soon." "Thank you, sir," said the man. "Don't go yet," then, putting a stick through the bars of the cage he lifted up the cat, when from beneath her out ran a white rat and three white mice. "Won-der-ful!" slowly ejaculated he of the burly form; "Wonder-ful!" The money was paid.

Cats, properly trained, will not touch anything, alive or dead, on the premises to which they are attached. I have known them to sport with tame rabbits, to romp and jump in frolicsome mood this way, then that, which both seemed greatly to enjoy, yet they would bring home wild rabbits they had killed, and not touch my little chickens or ducklings.

"The Old Lady"

When I built a house in the country, fond as I am of cats, I determined not to keep any there, because they would destroy the birds' nests and drive my feathered friends away, and I liked to watch and feed these from the windows. Things went pleasantly for awhile. The birds were fed, and paid for their keep with many and many a song. There were the old ones and there the young, and oft by the hour I watched them from the window; and they became so tame as scarcely caring to get out of my way when I went outside with more food. But - there is always a but - but one day, or rather evening, as I was "looking on," a rat came out from the rocks, and then another. Soon they began their repast on the remains of the birds' food. Then in the twilight came mice, the short-tailed and the long, scampering hither and thither. This, too, was amusing. In the autumn I bought some filberts, and put them into a closet upstairs, went to London, returned, and thought I would sleep in the room adjoining the closet. No such thing. As soon as the light was out there was a sound of gnawing - curb - curb - sweek! - squeek - a rushing of tiny feet here, there, and everywhere; thump, bump - scriggle, scraggle - squeek - overhead, above the ceiling, behind the skirting boards, under the floor, and - in the closet. I lighted a candle, opened the door, and looked into the repository for my filberts. What a hustling, what a scuffling, what a scrambling. There they were, mice in numbers; they "made for" some holes in the corners of the cupboard, got jammed, squeaked, struggled, squabbled, pushed, their tails making circles; push - push - squeak! - more jostling, another effort or two - squeak - squeak - gurgle - squeak - more struggling - and they were gone. Gone? Yes! but not for long. As soon as the light was out back they came. No! oh, dear no! sleep! no more sleep. Outside, I liked to watch the mice; but when they climbed the ivy and got inside, the pleasure entirely ceased. Nor was this all; they got into the vineries and spoilt the grapes, and the rats killed the young ducks and chickens, and undermined the building also, besides storing quantities of grain and other things under the floor. The result number one was, three cats coming on a visit. Farmyard cats - cats that knew the difference between chickens, ducklings, mice, and rats. Result number two, that after being away a couple of weeks, I went again to my cottage, and I slept undisturbed in the room late the play-ground of the mice. My chickens and ducklings were safe, and soon the cats allowed the birds to be fed in front of the window, though I could not break them of destroying many of the nests. I never NOTICED more fully the very great use the domestic cat is to man than on that occasion. All day my cats were indoors, dozy, sociable, and contented. At night they were on guard outside, and doubtless saved me the lives of dozens of my "young things." One afternoon I saw one of my cats coming towards me with apparent difficulty in walking. On its near approach I found it was carrying a large rat, which appeared dead. Coming nearer, the cat put down the rat. Presently I saw it move, then it suddenly got up and ran off. The cat caught it again. Again it feigned death, again got up and ran off, and was once more caught. It laid quite still, when, perceiving the cat had turned away, it got up, apparently quite uninjured, and ran in another direction, and I and the cat - lost it! I was not sorry. This rat deserved his liberty. Whether it was permanent I know not, as "Littlejohn," the cat, remained, and I left.

The cat is not only a very useful animal about the house and premises, but is also ornamental. It is lithe and beautiful in form, and graceful in action. Of course there are cats that are ugly by comparison with others, both in form, colour, and markings; and as there are now cat shows, at which prizes are offered for varieties, I will endeavour to give, in succeeding chapters, the points of excellence as regards form, colour, and markings required and most esteemed for the different classes. I am the more induced to define these as clearly as possible, owing to the number of mistakes that often occur in the entries.

Long-Haired Cats

Introduction, and A Deaf Cat

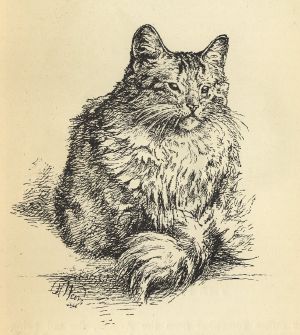

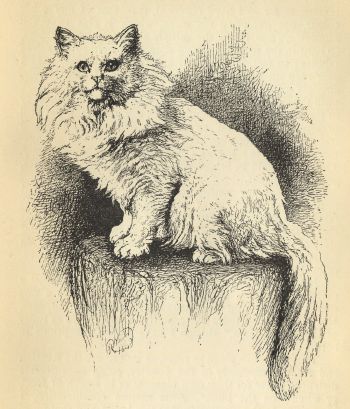

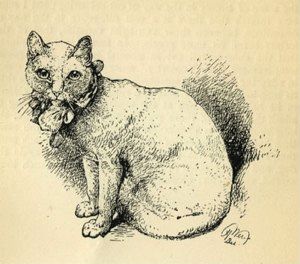

Miss F. Moore's Persian cat, "Fez"

A curious fact relating to the white cat of not only the long but also the short-haired breed is their deafness. Should they have blue eyes, which is the fancy colour, these are nearly always deaf; although I have seen specimens whose hearing was as perfect as that of any other colour. Still deafness in white cats is not always confined to those with blue eyes, as I too well know from purchasing a very fine male at the Crystal Palace Show some few years since. The price was low and the cat "a beauty," both in form, coat, and tail, his eyes were yellow, and he had a nice, meek, mild, expressive face. I stopped and looked at him, as he much took my fancy. He stared at me wistfully, with something like melancholy in the gaze of his amber-coloured eyes. I put my hand through the bars of the cage. He purred, licked my hand, rubbed against the wires, put his tail up, as much as to say, "See, here is a beautiful tail; am I not a lovely cat?" "Yes," thought I, "a very nice cat." When I looked at my catalogue and saw the low price, "something is wrong here," said I, musingly. "Yes, there must be something wrong. The price is misstated, or there is something not right about this cat." No! it was a beauty - so comely, so loving, so gentle - so very gentle. "Well," said I to myself, "if there is no misstatement of price, I will buy this cat," and, with a parting survey of its excellences, I went to the office of the show manager. He looked at the letter of entry. No; the price was quite right - "two guineas!" "I will buy it," said I. And so I did; but at two guineas I bought it dearly. Yes! very dearly, for when I got it home I found it was "stone" deaf. What an unhappy cat it was! If shut out of the dining-room you could hear its cry for admission all over the house; being so deaf the poor wretched creature never knew the noise it made. I often wish that it had so known - very, very often. I am satisfied that a tithe would have frightened it out of its life. And so loving, so affectionate. But, oh! horror, when it called out as it sat on my lap, its voice seemed to acquire at least ten cat power. And when, if it lost sight of me in the garden, its voice rose to the occasion, I feel confident it might have been heard miles off. Alas! he never knew what that agonised sound was like, but I did, and I have never forgotten it, and I never shall. I named him "The Colonel" on account of his commanding voice.

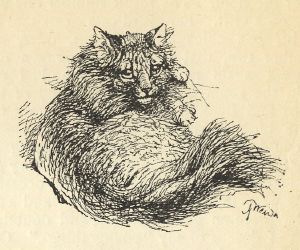

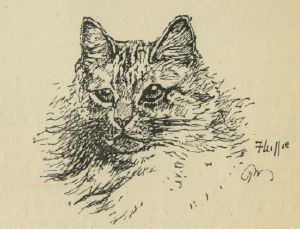

Miss Saunders' "Tiger"

One morning a friend came - blessed be that day - and after dinner he saw "the beauty." "What a lovely cat!" said he. "Yes," said I, "he is very beautiful, quite a picture." After a while he said, looking at "Pussy" warming himself before the fire, "I think I never saw one I liked more." " Indeed," said I, "if you really think so, I will give it to you; but he has a fault - he is 'stone' deaf." "Oh, I don't mind that," said he. He took him away - miles and miles away. I was glad it was so many miles away for two reasons. One was I feared he might come back, and the other that his voice might come resounding on the still night air. But he never came back nor a sound. - A few days after he left "to better himself," a letter came saying, would I wish to have him back? They liked it very much, all but its voice. "No," I wrote, "no, you are very kind, no, thank you; give him to any one you please - do what you will with 'the beauty,' but it must not return, never." When next I saw my friend, I asked him how "the beauty" was. "You dreadful man!" said he; "why, that cat nearly drove us all mad - I never heard anything like it." "Nor I," said I, sententiously. "Well," said my friend, "'all is well that ends well;' I have given it to a very deaf old lady, and so both are happy." "Very, I trust," said I.

"The Colonel", a deaf white Persian

The foregoing is by way of advice; in buying a white cat - or, in fact, any other - ascertain for a certainty that it is not deaf.

A short time since I saw a white Persian cat with deep blue eyes sitting at the door of a tobacconist's, at the corner of the Haymarket, London. On inquiry I found that the cat could hear perfectly, and was in no way deficient of health and strength; and this is by no means a solitary instance.

Miss Saunders' "Tiger"

The Angora

Miss Moore's "Dinah."

The Angora cat, as its name indicates, comes from Angora, in Western Asia, a province that is also celebrated for its goats with long hair, which is of extremely fine quality. It is said that this deteriorates when the animal leaves that locality. This may be so, but that I have no means of proving; yet, if so, do the Angora cats also deteriorate in the silky qualities of their fur? Or does it get shorter? Certain it is that many of the imported cats have finer and longer hair than those bred in this country; but when are the latter true bred? Even some a little cross-bred will often have long hair, but not of the texture as regards length and silkiness which is to be noted in the pure breed. The Angora cats, I am told, are great favourites with the Turks and Armenians, and the best are of high value, a pure white, with blue eyes, being thought the perfection of cats, all other points being good, and its hearing by no means defective. The points are a small head, with not too long a nose, large full eyes of a colour in harmony with that of its fur, ears rather large than small and pointed, with a tuft of hair at the apex, the size not showing, as they are deeply set in the long hair on the forehead, with a very full flowing mane about the head and neck; this latter should not be short, neither the body, which should be long, graceful, and elegant, and covered with long, silky hair, with a slight admixture of woolliness; in this it differs from the Persian, and the longer the better. In texture it should be as fine as possible, and also not so woolly as that of the Russian; still it is more inclined to be so than the Persian. The legs to be of moderate length, and in proportion to the body; the tail long, and slightly curving upward towards the end. The hair should be very long at the base, less so toward the tip. When perfect, it is an extremely beautiful and elegant object, and no wonder that it has become a pet among the Orientals. The colours are varied; but the black which should have orange eyes, as should also the slate colours, and blues, and the white are the most esteemed, though the soft slates, blues, and the light fawns, deep reds, and mottled grays are shades of colour that blend well with the Eastern furniture and other surroundings. There are also light grays, and what is termed smoke colour; a beauty was shown at Brighton which was white with black tips to the hair, the white being scarcely visible, unless the hair was parted; this tinting had a marvellous effect. I have never seen imported strong-coloured tabbies of this breed, nor do I believe such are true Angoras. Fine specimens are even now rare in this country, and are extremely valuable. In manners and temper they are quiet, sociable, and docile, though given to roaming, especially in the country, where I have seen them far from their homes, hunting the hedgerows more like dogs than cats; nor do they appear to possess the keen intelligence of the short-haired European cat. They are not new to us, being mentioned by writers nearly a hundred years ago, if not more. I well remember white specimens of uncommon size on sale in Leadenhall Market, more than forty years since; the price usually was five guineas, though some of rare excellence would realise double that sum.

The Persian Cat

This differs somewhat from the Angora, the tail being generally longer, more like a table brush in point of form, and is generally slightly turned upwards, the hair being more full and coarser at the end, while at the base it is somewhat longer. The head is rather larger, with less pointed ears, although these should not be devoid of the tuft at the apex, and also well furnished with long hair within, and of moderate size. The eyes should be large, full, and round, with a soft expression; the hair on the forehead is generally rather short in comparison to the other parts of the body, which ought to be clothed with long silky hair, very long about the neck, giving the appearance of the mane of the lion. The legs, feet, and toes should be well clothed with long hair and have well-developed fringes on the toes, assuming the character of tufts between them. It is larger in body, and generally broader in the loins, and apparently stronger made, than the foregoing variety, though yet slender and elegant, with small bone, and exceedingly graceful in all its movements, there being a kind of languor observable in its walk, until roused, when it immediately assumes the quick motion of the ordinary short-haired cat, though not so alert. The colours vary very much, and comprise almost every tint obtainable in cats, though the tortoiseshell is not, nor is the dark marked tabby, in my opinion, a Persian cat colour, but has been got by crossing with the short-haired tortoiseshell, and also English tabby, and as generally shows pretty clearly unmistakable signs of such being the case. For a long time, if not now, the black was the most sought after and the most difficult to obtain. A good rich, deep black, with orange-coloured eyes and long flowing hair, grand in mane, large and with graceful carriage, with a mild expression, is truly a very beautiful object, and one very rare. The best I have hitherto seen was one that belonged to Mr. Edward Lloyd, the great authority on all matters relating to aquariums. It was called Mimie, and was a very fine specimen, usually carrying off the first prize wherever shown. It generally wore a handsome collar, on which was inscribed its name and victories. The collar, as Mr. Lloyd used jocosely to observe, really belonged to it, as it was bought out of its winnings; and, according to the accounts kept, was proved also to have paid for its food for some considerable period. It was, as its owner laughingly said, "his friend, and not his dependent," and generally used to sit on the table by his side while he was writing either his letters, articles, or planning those improvements regarding aquariums, for which he was so justly celebrated.

Miss Saunders' very Light Blue Tabby, "Sylvie."

Next in value is the light slate or blue colour. This beautiful tint is very different in its shades. In some it verges towards a light purplish or lilac hue, and is very lovely; in others it tends to a much bluer tone, having a colder and harder appearance, still beautiful by way of contrast; in all the colour should be pure, even, and bright, not in any way mottled, which is a defect; and I may here remark that in these colours the hair is generally of a softer texture, as far as I have observed, than that of any other colour, not excepting the white, which is also in much request. Then follow the various shades of light tabbies, so light in the marking having scarcely a right to be called tabbies, in fact, tabby is not a Persian colour, nor have I ever seen an imported cat of that colour - I mean firmly, strongly marked with black on a brown-blue or gray ground, until they culminate in those of intense richness and density in the way of deep, harmonious browns and reds, yet still preserving throughout an extreme delicacy of line and tracery, never becoming harsh or hard in any of its arrangements or colour; not as the ordinary short-haired tabby. The eyes should be orange-yellow in the browns, reds, blues, grays, and blacks.

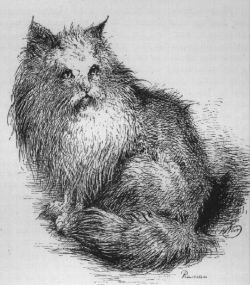

Mr. Lloyd's Black Persian, "Minnie."

As far as my experience extends, and I have had numerous opportunities of noticing, I find this variety less reliable as regards temper than the short-haired cats, less also in the keen sense of observing, as in the Angora, and also of turning such observations to account, either as regards their comfort, their endeavour to help themselves, or in their efforts to escape from confinement.In some few cases I have found them to be of almost a savage disposition, biting and snapping more like a dog than a cat, and using their claws less for protective purposes. Nor have I found them so "cossetty" in their ways as those of the "short-coats," though I have known exceptions in both.They are much given to roam, as indeed are the Russian and Angora, especially in the country, going considerable distances either for their own pleasure or in search of food, or when "on the hunt." After mature consideration, I have come to the conclusion that this breed, and slightly so the preceding, are decidedly different in their habits to the short-haired English domestic cat, as it is now generally called.

Mr. A. A. Clarke's White Persian, "Tim."

It may be, however, only a very close observer would notice the several peculiarities which I consider certainly exist. These cats attach themselves to places more than persons, and are indifferent to those who feed and have the care of them. They are beautiful and useful objects about the house, and generally very pleasant companions, and when kept with the short-haired varieties form an exceedingly pretty and interesting contrast; but, as I have stated, they certainly require more attention to their training, and more caution in their handling, than the latter. I may here remark, that during the time I have acted as judge at cat shows, which is now over eighteen years, it has been seldom there has been any display of temper in the short-haired breeds in comparison with the long; though some of the former, in some instances, have not comported themselves with that sweetness and amiability of disposition that is their usual characteristic. My attendant has been frequently wounded in our endeavour to examine the fur, dentition, etc., of the Angora, Persian, or Russian; and once severely by a "short-hair." Hitherto I have been so fortunate as to escape all injury, but this I attribute to my close observation of the countenance and expression of the cat about to be handled, so as to be perfectly on my guard, and to the knowledge of how to put my hands out of harm's way. If a vicious cat is to be taken from one pen to another, it must be carried by the loose skin at the back of the neck and that of the back with both hands, and held well away from the person who is carrying it.

Mrs. C. Herring's young

Persian Kitten

The Russian Long-Haired Cat

The above is a portrait of a cat given me many years ago, whose parents came from Russia, but from what part I could never ascertain. It differed from the Angora and the Persian in many respects. It was larger in body with shorter legs. The mane or frill was very large, long, and dense, and more of a woolly texture, with coarse hairs among it ; the colour was of dark tabby, though the markings were not a decided black, nor clear and distinct ; the ground colour was wanting in that depth and richness possessed by the Persian, having a somewhat dull appearance. The eyes were large and prominent, of a bright orange, slightly tinted with green, the ears large by comparison, with small tufts, full of long, woolly hair, the limbs stout and short, the tail being very dissimilar, as it was short, very woolly, and thickly covered with hair the same length from the base to the tip, and much resembled in form that of the English wild cat.

Its motion was not so agile as other cats, nor did it apparently care for warmth, as it liked being outdoors in the coldest weather. Another peculiarity being that it seemed to care little in the way of watching birds for the purpose of food, neither were its habits like those of the short-haired cats that were its companions. It attached itself to no person, as was the case with some of the others, but curiously took a particular fancy to one of my short-haired, silver-gray tabbies ; the two appeared always together. In front of the fire they sat side by side. If one left the room the other followed. Adown the garden paths there they were, still companions ; and at night slept in the same box ; they drank milk from the same saucer, and fed from the same plate, and, in fact, only seemed to exist for eachother. In all my experience I never knew a more devoted couple.

I bred but one kitten from the Russian, and this was the offspring of the short-haired silver tabby. It was black-and-white, and resembled the Russian in a large degree, having a woolly coat, somewhat a mane, and a short, very bushy tail. This, like his father, seemed also to be fonder of animals for food than birds, and, although very small, would without any hesitation attack and kill a full-grown rat.

I have seen several Russian cats, yet never but on this occasion had the opportunity of comparing their habits and mode of life with those of the other varieties ; neither have I seen any but those of a tabby colour, and they mostly of a dark brown. I am fully aware that many cross-bred cats are sold as Russian, Angora, and Persian, either between these or the short-haired, and some of these, of course, retain in large degree the distinctive peculiarities of each breed. Yet to the practised eye there is generally - I do not say always - a difference of some sort by which the particular breed may be clearly defined. When the prizes are given, as is the case even at our largest cat shows, for the best long-haired cat, there, of course, exists in the eye of the judge no distinction as regards breed. He selects, as he is bound to do, that which is the best *long-haired* cat in all points, the length of hair, colour, texture, and condition of the exhibit being that which commands his first attention. But if it were so put that the prize should be for the best Angora, Persian, Russian, etc., it would make the task rather more than difficult, for I have seen some "first-cross cats" that have possessed all, or nearly all, the points requisite for that of the Angora, Persian, or Russian, while others so bred have been very deficient, perhaps showing the Angora cross only by the tail and a slight and small frill. At the same time it must be noted, that, although from time to time some excellent specimens may be so bred, it is by no means desirable to buy and use such for stock purposes, for they will in all probability "throw back" - that is, after several generations, although allied with thoroughbred, they will possibly have a little family of quite "short-hairs." I have known this with rabbits, who, after breeding short-haired varieties for some time, suddenly reverted to a litter of "long-hairs" ; but have not carried out the experiment with cats. At the same time I may state that I have little or no doubt that such would be the case ; therefore I would urge on all those who are fond of cats - or, in fact, other animals - of any any particular breed, to use when possible none but those of the purest pedigree, as this will tend to prevent much disappointment that might otherwise ensue. But I am digressing, and so back to my subject - the Russian long-haired cat. I advisedly say long-haired cat, for I shall hereafter have to treat of other cats coming from Russia that are short-haired, none which I have hitherto seen being tabbies, but whole colour. This is the more singular as all those of the long-hair have been brown tabbies, with only one or two exceptions, which were black. It is just possible these were the offspring of tabby or gray parents, as the wild rabbit has been known to have had black progeny. I have seen a black rabbit shot from amongst the gray on the South Downs.

I do not remember having seen a white Russian "long-hair," and I should feel particularly obliged to any of my readers who could supply me with further information on this subject, or on any other relating to the various breeds of cats, cat-life and habits. I am fully aware that no two cats are exactly alike either in their form, colour, movements, or habits ; but what I have given much study and attention to, and what I wish to arrive at is, the broad existing natural distinctions of the different varieties. In this way I shall feel grateful for any information.

Long-Haired Cats

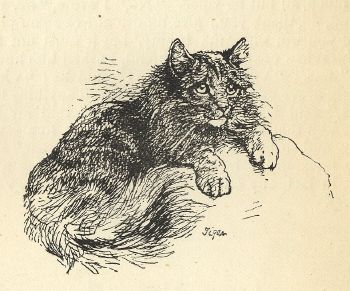

Miss Mary Gresham's Persian kitten, "Lambkin No. 2."

I have now concluded my remarks on the long-haired varieties of cats that I am at present acquainted with. They are an exceedingly interesting section ; their habits, manners, forms, and colours form a by no means unprofitable study for those fond of animal life, as they, in my opinion, differ in many ways from those of their "short-haired" brethren. I shall not cease, however, in my endeavours to find out if any other long-haired breeds exist, and I am, therefore, making inquiries in every direction in which I deem it likely I shall get an increase of information on the subject, but hitherto without any success. Therefore, I am led to suppose that the three I have enumerated are the only domesticated long-haired varieties. The nearest approach, I believe, to these in the wild state is that of the British wild cat, which has in some instances a mane and a bushy tail, slightly resembling that of the Russian long-hair, with much of the same facial expression, and rather pointed tufts at the apex of the ears. It is also large, like some of the "long-haired" cats that I have seen ; in fact, it far more resembles these breeds than those of the short hair.

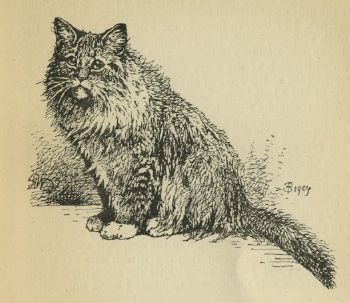

Miss Moore's "Bogey."

I was much struck with the many points of similitude on seeing the British wild cat exhibited by the Duke of Sutherland at the first cat show at the Crystal Palace in July, 1871. I merely offer this as an idea for further consideration. At the same time, allow me to say that I have had no opportunity of studying the anatomy of the British wild cat, in contradiction to that of the Russian, or others with long hair. I only wish to point out what I term a general resemblance, far in excess of those with short hair. I am fully aware how difficult it is to trace any origin of the domestic cat, or from what breed ; it is also said, that the British wild cat is not one of them, still I urge there exists the similarity I mention ; whether it is so apparent to others I do know not.

Short-Haired Cats

The Tortoiseshell Cat

I now come to the section of the short-haired domestic cat, a variety possessing sub-varieties. Whether these all came from the same origin is doubtful, although in breeding many of the different colours will breed back to the striped or tabby colour, and, per contra, white whole-coloured cats are often got from striped or spotted parents, and vice versâ. Those that have had any experience of breeding domesticated animals or bird, know perfectly well how difficult it is to keep certain peculiarities gained by years of perseverance of breeding for such points of variation, or what is termed excellence. Place a few fancy pigeons, for instance, in the country and let them match how they like, and one would be quite surprised, unless he were a naturalist, to note the great changes that occur in a few years, and the unmistakable signs of reversion towards their ancestral stock - that of the Rock pigeon. But with the cat this is somewhat different, as little or no attempts have been made, as far as I know of, until cat shows were instituted, to improve any particular breed either in form or colour. Nor has it even yet, with the exception of the long-haired cats. Why this is so I am at a loss to understand, but the fact remains. Good well-developed cats of certain colours fetch large prices, and arer, if I may use the term, perpetual prize-winners. I will take as an instance the tortoiseshell tom, he, or male cat as one of the most scarce, and the red or yellow tabby she-cat as the next ; and yet the possessor of either, with proper care and attention, I have little or no doubt, has it in his power to produce either variety ad libitum. It is now many years since I remember the first "tortoiseshell tom-cat ;" nor can I now at this distance of time quite call to mind whether or not it was not a tortoiseshell-and-white, and not a tortoiseshell pure and simple. It was exhibited in Piccadilly. If I remember rightly, I made a drawing of it, but as it is about forty years ago, of this I am not certain, although I have lately been told that I did, and that the price asked for the cat was 100 guineas.

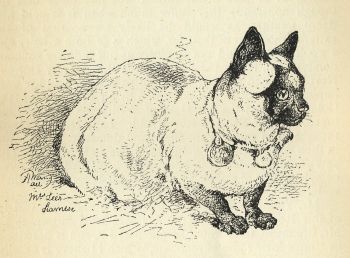

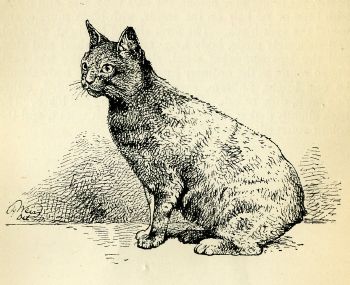

Mr. Smith's prize he-cat.

This supposed scarcity was rudely put aside by the appearance, at the Crystal Palace Show of 1871, of no less than one tortoiseshell he-cat (exhibited by Mr. Smith) and three tortoiseshell-and-white he-cats, but it will be observed there was really but only one tortoiseshell he-cat, the others having white. On referring to the catalogues of the succeeding shows, no other pure tortoiseshell has been exhibited, and he ceased to appear after 1873 ; but tortoiseshell-and-white have been shown from 1871, varying in number from five to three until 1885. One of these, a tortoiseshell-and-white belonging to Mr. Hurry, gained no fewer than nine first prizes at the Crystan Palace, besides several firsts at other shows ; this maintains my statement, that a really good scarce variety of cats is a valuable investment, Mr. Hurry's cat Totty keeping up his price of £100 till the end.

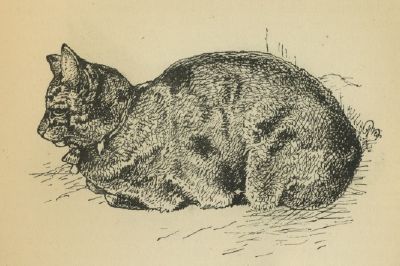

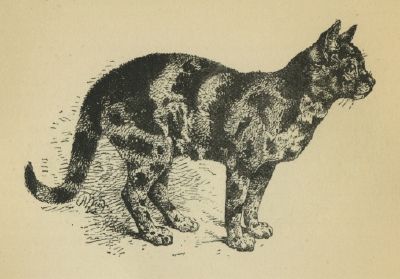

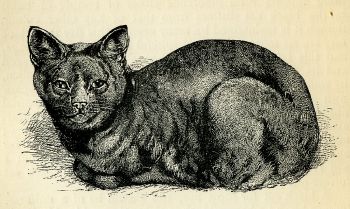

Example of tortoiseshell cat, very dark variety.

As may have been gathered from the foregoing remarks, the points of the tortoiseshell he-cat are, black-red and yellow in patches, but no white. The colouring should be in broad, well-defined blotches and solid in colour, not mealy or tabby-like in the marking, but clear, sharp, and distinct, and the richer and deeper the colours the better. When this is so the animal presents a very handsome appearance. The eyes should be orange, the tail long and thick towards the base, the form slim, graceful, and elegant, and not too short on the leg, to which this breed has a tendency. Coming then to the actual tortoiseshell he, or male cat without white, I have never seen but one at the Shows, and that was exhibited by Mr. Smith. It does not appear that Mr. Smith bred any from it, nor do I know whether he took any precautions to do so ; but if not, I am still of the opinion that more might have been produced. In Cassell's "Natural History," it is stated that the tortoiseshell cat is quite common in Egypt and in the south of Europe. This I can readily believe, as I think that it comes from a different stock than the usual short-haired cat, the texture of the hair being different, the form of tail also. I should much like to know whether in that country, where the variety is so common, there exists any number of tortoiseshell he-cats. In England the he-kittens are almost invariably red-tabby or red-tabby-and-white ; the red-tabby she-cats are almost as scarce as tortoiseshell-and-white he-cats. Yet if red-tabby she-cats can be produced, I am of the opinion that tortoiseshell he-cats could also. I had one of the former, a great beauty, and hoped to perpetuate the breed, but it unfortunately fell a victim to wires set by poachers for game. Again returning to the tortoiseshell, I have noted that, in drawings made by the Japanese, the cats are always of this colour ; that being so, it leads one to suppose that in that country tortoiseshell he-cats must be plentiful. Though the drawings are strong evidence, they are not absolute proof. I have asked several travelling friends questions as regards the Japanese cats, but in no case have I found them to have taken sufficient notice for their testimony to be anything else than worthless. I shall be very thankful for any information on this subject, for to myself, and doubtless also to many others, it is exceedingly interesting. Any one wishing to breed rich brown tabbies, should use a tortoiseshell she-cat with a very brown and black-banded he-cat. They are not so good from the spotted tabby, often producing merely tortoiseshell tabbies instead of brown tabbies, or true tortoiseshells. My remarks as to the colouring of the tortoiseshell he-cats are equally applicable to the she-cat, which should not have any white. Of the tortoiseshell-and-white hereafter.

To breed tortoiseshell he-cats, I should use males of a whole colour, such as either white, black, or blue ; and on no account any tabby, no matter the colour. What is wanted is patches of colour, not tiny streaks or spots ; and I feel certain that, for those who persevere, there will be successful results.

The Tortoiseshell-And-White Cat

This is a more common mixture of colouring than the tortoiseshell pure and simple without white, and seems to be widely spread over different parts of the world. It is the opinion of some that this colour and the pure tortoiseshell is the original domestic cat, and that the other varieties of marking and colours are but deviations produced by crossing with wild varieties. My brother, John Jenner Weir, F.L.S., F.Z.S., holds somewhat to this opinion ; but, to me, it is rather difficult to arrive at this conclusion. In fact, I can scarcely realise the ground on which the theory is based - at the same time, I do not mean to ignore it entirely. And yet, if this be so, from what starting-point was the original domestic cat derived, and by what means were the rich and varied markings obtained? I am fully aware that by selection cats with large patches of colour may be obtained ; still, there remain the peculiar markings of the tortoiseshell. Nor is this by any means an uncommon colour, not only in this country, but in many others, and there also appears to be a peculiar fixedness of this, especially in the female, but why it is not so in the male I am at loss to understand, the males almost invariably coming either red-tabby or red-tabby-and-white. One would suppose that black or white would be equally likely ; but, as far as my observations take me, this is not so, though I have seen both pure white, yellow, red, and black in litters of kittens, but this might be different were the he parent tortoiseshell.

Some years ago I was out with a shooting party not far from Snowdon, in Wales, when turning past a large rock I came on a sheltered nook, and there in a nest made of dry grasses laid six tortoiseshell-and-white kittens about eight to ten days old. I was much surprised at this, as I did not know of any house near, therefore these must have been the offspring of some cat or cats that were leading a roving or wild life, and yet it had no effect as to the deviation of the colour. I left them there, and without observing the sex. I was afterwards sorry, as it is just possible, though scarcely probable, that one or more of the six, being all of the same colour, might have proved to be a male. As I left the neighbourhood a few days after I saw no more of them, nor have I since heard of any being there ; so conclude they in some way were destroyed.

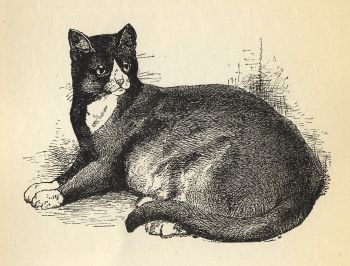

I have observed in the breed of tortoiseshell or tortoiseshell-and-white that the hair is of a coarser texture than the ordinary domestic cat, and that the tail is generally thicker especially at the base, though some few are thin-tailed ; yet I prefer the thick and tapering form. Some are very much so, and of good length ; the legs are generally somewhat short ; I do not ever remember seeing a really long-legged tortoiseshell, though when this is so if not too long it adds much to its grace of action. I give a drawing of what I consider to be a GOOD tortoiseshell-and-white tom or he-cat. It will be observed that there is more white on the chest, belly, and hind legs than is allowable in the blacl-and-white cat. This I deem necessary for artistic beauty, when the colour is laid on in patches, although it should be even, clear, and distinct in its outline ; the larger space of white adds brilliancy to the red, yellow, and black colouring. The face is one of the parts which should have some uniformity of colour, and yet not so, but a mere balancing of colour ; that is to say, that there should be a relief in black, with the yellow and red on each side, and so in the body and tail. The nose should be white, the eyes orange, and the whole colouring rich and varied without the least Tabbyness, either brown or gray or an approach to it, such being highly detrimental to its beauty.

I have received a welcome letter from Mr. Herbert Young, of James Street, Harrogate, informing me of the existence of what is said to be a tortoiseshell tom or he-cat somewhere in Yorkshire, and the price is fifty guineas ; but he, unfortunately, has forgotten the exact address. He also kindly favours me with the further information of a tortoiseshell-and-white he-cat. He describes it as "splendid," and "extra good in colour," and it is at present in the vicinity of Harrogate. And still further, Mr. Herbert Young says, "I am breeding from a dark colour cat and two tortoiseshell females," and he hopes, by careful selection, to succeed in "breeding the other colour out." This, I deem, is by no means an unlikely thing to happen, and, by careful management, may not take very long to accomplish ; but much depends on the ancestry, or rather the pedigree of both sides. I for one most heartily wish Mr. Herbert Young success, and it will be most gratifying should he arrive at the height of his expectations. Failing the producing of the desired colour in the he-cats by the legitimate method of tortoiseshell with tortoiseshell, I would advise the trial of some whole colours, such as solid black and white. This may prove a better way than the other, as we pigeon fanciers go an apparently roundabout way often to obtain what we want to attain in colour, and yet there is almost a certainty in the method.

As regards the tortoiseshell cat, there is a distinct variety known to us cat fanciers as the tortoiseshell-tabby. This must not be confounded with the true variety, as it consists only of a variegation in colour of the yellow, the red, and the dark tabby, and is more in lines than patches, or patches of lines or spots. These are by no means ugly, and a well-marked, richly-coloured specimen is really very handsome. They may also be intermixed with white, and should be marked the same as the true tortoiseshell ; but in competition with the real tortoiseshell they would stand no chance whatever, and ought in my opinion to be disqualified as being wrong class, and be put in that for "any other colour."

The Brown Tabby Cat

[Typed in by Martina Šiljeg, Delta Pelegrino cattery]

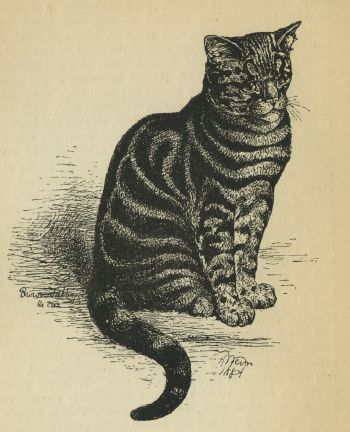

THE tabby cat is doubtless one of, if not the most common of colours, and numbers many almost endless varieties of both tint and markings. Of these those with very broad bands of black, or narrow bands of black, on nearly a black ground, are usually called black tabby, and if the bands are divided into spots instead of being in continuous lines, then it is a spotted black tabby; but I purpose in this paper to deal mostly with the brown tabby-that is to say, a tabby, whose ground colour is of a very rich, orangey, dark brown ground, without any white, and that is evenly, proportionably, and not too broadly but elegantly marked on the face, head, breast, sides, back, belly, legs, and tail with bands of solid, deep, shining black. The front part of the head or face and legs, breast, and belly should have a more rich red orange tint than the back, but which should be nearly if not equal in depth of colour, though somewhat browner; the markings should be graceful in curve, sharply, well, and clearly defined, with fine deep black edges, so that the brown and black are clear and distinct the one from the other, not blurred in any way. The banded tabby should not be spotted in any way, excepting those few that nearly always occur on the face and sometimes on the fore-legs. The clearer, redder, and brighter the brown the better. The nose should be deep red, bordered with black; the eyes an orange colour, slightly diffused with green; in form the head should not be large, nor too wide, being rather longer than broad, so as not to give too round or clumsy an apperance; ears not large nor small, but of moderate size, and of good form; legs medium length, rather long than short, so as not to lose grace of action; body long, narrow, and deep towards the fore part. Tail long, and gradually tapering towards the point; feet round, with black claws, and black pads; yellowish-white around the black lips and brown whiskers are allowable, but orange.tinted are far preferable, and pure white should disqualify. A cat of this description is now somewhat rare. What are generally shown as brown tabbies are not sufficiently orange-brown, but mostly of a dark, brownish-gray. This is simply the ordinary tabby, and not the brown tabby proper.

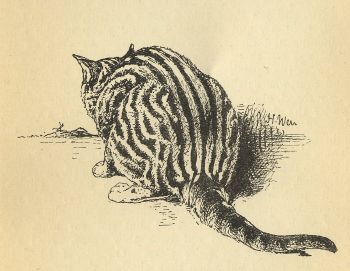

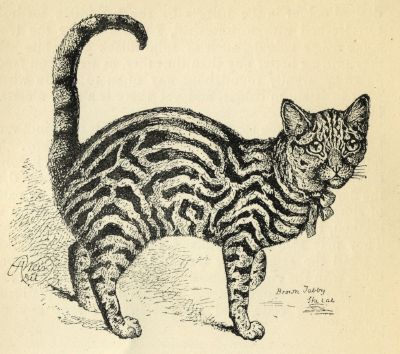

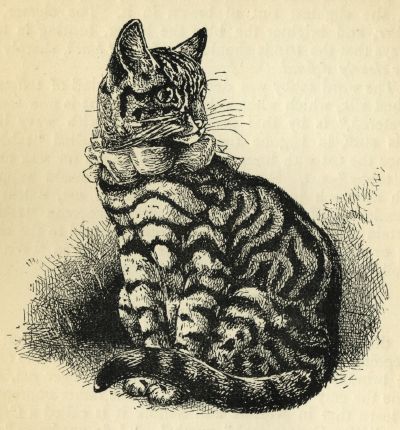

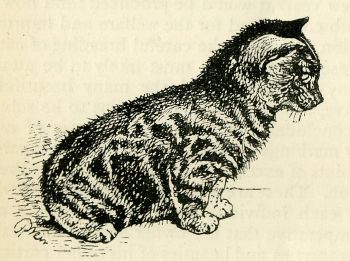

Brown tabby - bars the right width.

As I stated in my notes on the Tortoiseshell cat, the best parents to obtain a good brown tabby from is to have a strongly marked, not too broad-banded tabby he-cat and a tortoiseshell she-cat with little black, or red tabby she-cat, the produce being, when tabby, generally of a rich brown, or sometimes what is termed black tabby, and also red tabby. The picture illustrating these notes is from one so bred, and is a particularly handsome specimen.

There were two he-cats in the litter, one the dark-brown tabby just mentioned, which I named Aaron, and the other, a very fine red tabby, Moses. This last was even a finer animal than Aaron, being very beautiful in colour and very large in size; but he, alas! Like many others, was caught in wires set by poachers, and was found dead.

His handsome brother still survives, though no longer my property. The banded red tabby should be marked precisely the same as the brown tabby, only the bands should be of deep red on an orange ground, the deeper in colour the better; almost a chocolate on orange se very fine. The nose deep pink, as also the pads of the feet. The ordinary dark tabby the same way as the brown, and so also the blue or silver, only the ground colour should be of a pale, soft, blue colour - not the slightest tint of brown in it. The clearer, the lighter, and brighter the blue the better, bearing in mind always that the bands should be of a jet black, sharply and very clearly defined.

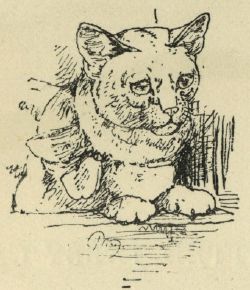

Brown tabby - markings much too wide.

The word tabby was derived from a kind of taffeta, or ribbed silk, which when calendered or what is now termed 'watered', is by that process covered with wavy lines. This stuff, in bygone times, was often called 'tabby:' hence the cat with lines or markings on its fur was called a 'tabby' cat. But it might also, one would suppose, with as much justice, be called a taffety cat, unless the calendering of 'taffety' caused it to become 'tabby.' Certain it is that the word tabby only referred to the mark-ing or stripes, not to the absolute colour, for in 'Wit and Drollery' (1682), p. 343, is the following:-

'Her petticoat of satin,

Her gown of crimson tabby.'

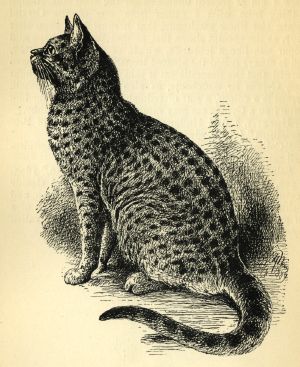

Well-marked prize silver tabby.

So I referred to my Bailey's Dictionary of 1730, and there, 'sure enough,' was the elucidation; for I found that Cyprus was a kind of cloth made of silk and hair, showing wavy lines on it, and coming from Cyprus; therefore this somewhat strengthens the argument in favour of 'taffeta,' or 'tabby,' but it is still curious that the Norfolk and Suffolk people should have adopted a kind of cloth as that representing the markings and colour of the cat, and that of a different name from that in use for the cat-one or more counties calling it a 'tabby cat,' as regards colour, and the other naming the same as 'Cyprus'. I take this to be exceedingly interesting. How or when such naming took place I am at present unable to get the least clue, though I think form what I gather from one of the Crystal Palace Cat Show catalogues, that it must have been after 1597, as the excerpt shows that at that time the shape and colour was like a leopard's, which, of course, is spotted, and is always called the spotted leopard. (Since this I have learned that the domestic cat is said to have been brought from Cyprus by merchants, as also was the tortoiseshell. Cyprus is a colour, a sort of reddish-yellow tabby.)

However, I find Holloway, in his 'Dictionary of Provincialisms' (1839), gives the following:-

'Calimanco Cat, s. (calimanco, a glossy stuff), a tortoiseshell cat, Norfolk.'

Salmon, in 'The Compleat English Physician,' 1693, p. 326, writing of the cat, says: 'It is a neat and cleanly creature, often licking itself to keep it fair and clean, and washing its face with its fore feet; the best are such as of a fair and large kind and of an exquisite tabby color called Cyprus cats'.

The Spotted Tabby

[Typed in by Martina Šiljeg, Delta Pelegrino cattery]

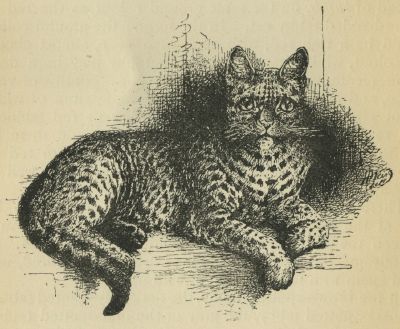

I HAVE thought it best to give two illustrations of the peculiar markings of the spotted tabby, or leopard cat of some, as showing its distinctness from the ordinary and banded Tabby, one of my reasons being that I have, when judging at cat shows, often found excellent specimens of both entered in the 'wrong class', thereby losing all chance of a prize, though, if rightly entered, either might very possibly have taken honours. I therefore wish to direct particular attention to the spotted character of the markings of the variety called the 'spotted tabby'. It will be observed that there are no lines, but what are lines in other tabbies are broken up into a number of spots, and the more these spots prevail, to the exclusion of lines or bands, the better the specimen is considered to be. The varieties of the ground colour or tint on which these markings or spots are placed constitutes the name, such as black-spotted tabby or yellow-spotted tabby in she-cats being by far the most scarce. These should be marked with spots instead of bands, on the same ground colour as the red or yellow-banded tabby cat. In the former the ground colour should be a rich red, with spots of a deep, almost chocolate colour, while that of the yellow tabby may be a deep yellow cream, with yellowish-brown spots. Both are very scarce, and are extremely pretty. Any admixture of white is not allowable in teh class for yellow or red tabbies; such exhibit must be put into the class (should there be one, which is usually the case at large shows) for red or yellow and white tabies. This exhibitors will do well to make a note of.

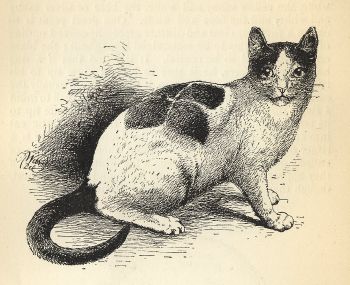

Spotted tabby cat.

There is a rich-coloured brown tabby hybrid to be seen at the Zoological Society Gardens in Regent's Park, between the wild cat of Bengal and a tabby she-cat. It is handsome, but very wild. These hybrids, I am told, will breed again with tame variety, or with others.

In the brown-spotted tabby, the dark gray-spotted tabby, the black-spotted tabby, the gray or the blue-spotted tabby, the eyes are best yellow or orange tinted, with the less of the green the better. The nose should be of a dark red, edged with black or dark brown, in the dark colours, or somewhat lighter colour in the gray or blue tabbies. The pads of the feet in all instances must be black. In the yellow and the red tabby the nose and the pads of the feet are to be pink. As regards the tail, that should have large spots on the upper and lower sides instead of being annulated, but this is difficult to obtain. It has always occurred to me that the spotted tabby is a much nearer approach to the wild English cat and some other wild cats in the way of colour than the ordinary broad-banded tabby. Those specimens of the crosses, said to be between the wild and domestic cat, that I have seen, have had a tendency to be spotted tabbies.

And these crosses were not infrequent in bygone times when the wild cats were more numerous than at present, as is stated to be the case by that reliable authority, Thomas Bewick. In the year 1873, there was a specimen shown at the Crystal Palace Cat Show, and also the last year or two there has been exhibited at the same place a most beautiful hybrid between the East Indian wild cat and the domestic cat. It was shown in the spotted tabby class, and won the first prize. The ground colour was a deep blackish-brown, with well-defined black spots, black pads to the feet, rich in colour, and very strong and powerfully made, and not by any means a sweet temper. It was a he-cat, ant though I have made inquiry, I have not been able to ascertain that any progeny has been reared from it, yet I have been informed that such hybrids between the Indian wild cat and the domestic cat breed freely.

The Abyssinian